John Copp is a former software engineer, frequent fisherman, screenwriter, poet and political activist I have the privilege of knowing through my writing group. He read some poetry at Three Mugs Brewing last weekend, and absolutely did not get me in a fistfight at last year’s Fisher Poets’ Gathering in Astoria.

John Copp is a former software engineer, frequent fisherman, screenwriter, poet and political activist I have the privilege of knowing through my writing group. He read some poetry at Three Mugs Brewing last weekend, and absolutely did not get me in a fistfight at last year’s Fisher Poets’ Gathering in Astoria.

Here he applies software design to screenwriting. Enjoy.

Time runs away faster than a frightened antelope. I wrote the original screenplay in four months. The next rewrite took eight months. Too long. Self, I said, take what you know about software design and apply it to screenplay design. Graduate degree in Computer Science, years in the industry, and over two million lines of code to my credit. So I did and finished the third rewrite in four weeks. Not a quick polish but a full rewrite. Two concepts helped: set theory and modular design.

I’m not talking about movie sets but mathematical sets. A set is a collection of related things:

- {apples, oranges, bananas} fruits

- {open a file, write to a file, close a file} software operations

- {hero, ally, opponent} screenplay archetypes

Sets provide a means of organizing large collections. The human intellect uses sets to manipulate ideas, perceptions, relationships, and strategies. In a sense, the human imagination is structured like a nested Russian doll. One set contains another which contains another. Given the number of neurons in the cerebral cortex, the number of nested sets is infinite.

Likewise, the pathways and possibilities a writer’s mind can explore are infinite. That poses a problem. If the number of options is infinite, and the life of a writer is finite, how to impose constraints so that something tangible – a deliverable product – gets created quickly? Sets to the rescue.

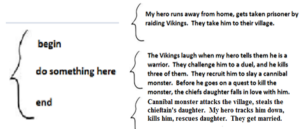

TOOLS: whiteboard, eraser, dry erase marker, and left curly braces. Each curly brace contains a set of related things, most commonly verbs. Software is all about action, and verbs perform actions. Same with screenplays. Here’s an example:

Voila! A screenplay. The 13th Warrior, more or less.

Each curly brace contains a set consisting of things (actors, events, circumstances) and, most likely, more curly braces, each of which contains a set of other things including more curly braces. “Cannibal monster attacks the village,” for instance, will expand into a set of related actions, each contained within a curly brace. Dolls within dolls within dolls.

Careful. You’re not writing the screenplay here. Just stubs with a few action verbs, maybe a character name or two. Be playful. It’s all erasable, movable, rewriteable. When you’re think you’ve got a good map, take a snapshot of the whiteboard and save it.

Now to modular design. Over two-thirds of the total cost of software systems is incurred after the software is released to the public. Why? The software is full of defects. The best antidote is modular design. A “program” becomes a set of separate, smaller pieces. The following characteristics help ensure that these modules behave well.

- Clarity of purpose: a module (or scene) should perform a limited set of precisely defined functions. Similarly, a well-crafted scene has a clear purpose: drive the story forward, say.

- Simplicity: a module should neither be overly long or overly complex. It’s behavior should have strict limitations. Limited inputs, limited scope of action, and limited output. In other words, it does what it is intended to do without throwing any surprises.

- Easily modified: a module should allow a straight-forward rewrite, not just by the author, but by whomever does the rewrite.

- Robust: a module should be able to take a beating in the hurly-burly of the real world without rolling over and crashing the whole system. Even better if it’s designed for testability. That is, it’s designed for a ruthless pounding by peers, critics, and script consultants.

- Interoperable: modules must play nicely in the sandbox with the other children. A rogue module that does its thing at the expense of other modules causes trouble. A scene that undercuts the credibility of the hero undercuts the credibility of the story.

- Aesthetic: a well-crafted module has a logical beauty that reflects thoughtfulness and mastery.

So let’s review.

STEP-BY-STEP

- TOOLS: whiteboard, eraser, dry erase marker, sticky notes in various colors.

- Write ACT I, ACT II, and ACT III on the whiteboard.

- Populate each act with stubs on the whiteboard.

- Take a snapshot with your cell phone. Save it.

- Erase the stubs but leave the act headers.

- Open or print the snapshot showing all the stubs.

- Using sticky notes, create scene hints, and post under the relevant act.

Cautionary note: by “hint”, I mean just a simple reminder. Here’s an example.

ALASKA STATE TROOPER

Interrogates Joe, accuses him of blowing up his own boat.

- When each act is populated with scene hints, stand back, review, think. Let it sit overnight.

- Take a snapshot of the whiteboard. Save it. Print it if you like.

- Next morning, scrutinize the whiteboard. You’ll be surprised how many holes jump out.

- Do a walk-through on what’s on the whiteboard. Talk aloud to yourself while you do it.

- Do another walk-through while explaining it to somebody else. Record critical comments.

- Do NOT fire up Final Draft until you are absolutely certain you’re on the right path.

- Take the rest of the day off. So something fun.

Now it’s time to implement each sticky note as a scene. Don’t be surprised if you replace or delete many sticky notes. It’s a discovery process. Put a checkmark on each sticky note when the scene is complete. It help spot gaps and, when the last one is checked, gives you a wonderful warm feeling.

Filling an empty sheet of paper with words is both challenging and great fun. When the words become thousands, however, and the pages number in the hundreds, it is easy to lose perspective. Key threads dangle in the air like unfinished spider webs. Unwanted redundancy and sloppy logic lurk in the shadows. Applying logical design is like shining a spotlight on a frog’s face: now you can see all the bumps. It’s a small price to pay to produce a higher quality product in a shorter period of time.